This story, recently written by Maury White, was constructed from information contained

in a letter he wrote to his mother a few days after the Cabildo made it through

the typhoon to reach Okinawa.

The Cabildo arrived in Buckner Bay on Aug. 30, 1945, joining a

mighty armada assembled for what would have been the occupational landing in Japan.

This consisted of five battleships, light and heavy cruisers, destroyers, etc.

On Sept. 9, in company with the Montpelier, Lunga Point,

Sanctuary and Consolation, we started the journey for the

occupational landings at Wakanoura Bay, Honshu, Japan. That

night, for the first time in Pacific waters, the ship sailed with lights

on. It was a strange feeling.

The final 30 miles to anchorage on Sept. 11 was a slow, tense,

grueling journey as the ships proceeded single file through

dangerous waters. The Nipponese harbor pilot aboard our ship

spoke English fluently but had scant knowledge of mine field

locations, particularly those laid from U.S. B-29 bombers.

A short trip that started at high noon wasn’t concluded until dusk.

Binoculars were at a premium as everyone wanted to check out the

Japanese lining the beach who were checking out their conquerors.

That night, and for the rest of this stay, four armed guards patrolled

the deck and two with machine guns circled the ship in a boat all

through the hours of darkness.

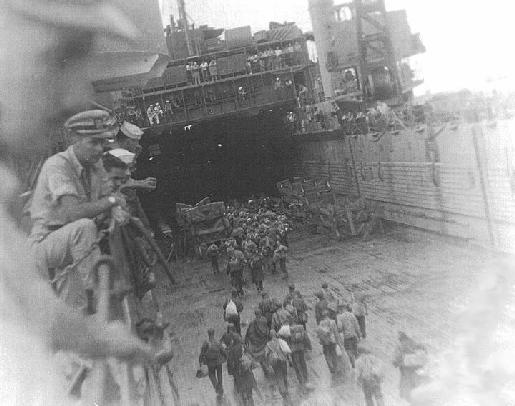

The next morning, the Cabildo’s boat pool shoved into high gear,

furnishing transportation for all ships as personnel and equipment

was landed in preparation for taking on men who had been

prisoners of war for over three years.

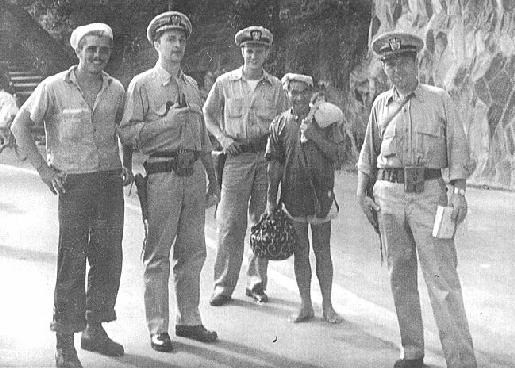

Non-official visits to the beach were discouraged but, in the usual

American can-do tradition, Navy personnel showed considerable

ingenuity in declaring selves "official."

Once ashore, it was a mob scene, although a controlled mob scene.

Whenever the hundreds of curious citizens edged too close to

where Japanese Red Cross nurses tended to the weakest of the

POWs, city policemen strolled toward the crowd, twirling what

appeared a heavy rope with a knot at the end. The crowd would

quickly retreat, then edge back again.

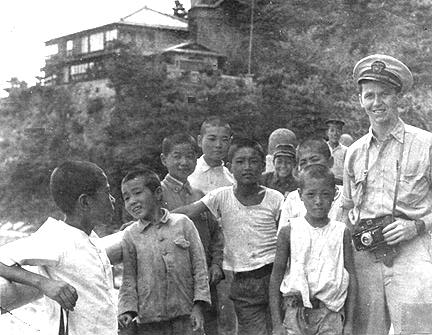

Because of the language barrier and atmosphere of fear, there was

little communication with Japanese adults. Children are children

everywhere, though, and Yanks who made the beach that day were

often surrounded by youngsters wanting to see, touch, and

enthusiastically beg candy and cigarettes from strangers not acting

like devils.

Hundreds of healthier POWs were also milling about, mostly

Dutch and Australian with a lesser number of Yanks and Javanese.

The English-speaking men, eager to visit, were starved for news of

their homelands and what had actually transpired to bring such a

sudden end to a long, long war.

One told Lt. Maury White the surrender had never been announced

at his camp, with word arriving by leaflets dropped from a U.S.

plane. Another’s group was informed the war was

temporarily suspended, but not to get the idea it was over.

At all camps, however, work details had been discontinued, food

and treatment upgraded, and several men spoke of getting

going-away presents from their former guards. Enlisted men had

generally been better fed than officers, the officers not being

assigned to heavy work duties.

All POWs were brought to a nearby hotel for delousing,

debriefing, and the best food they’d had since prior to capture.

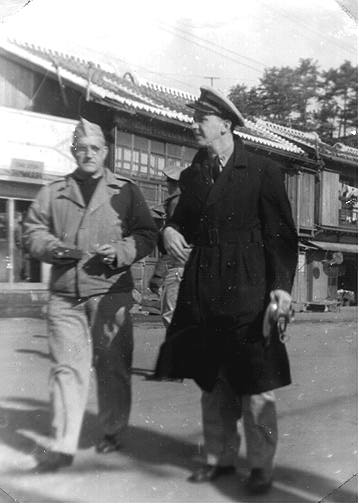

During their trek on the beach, posing as official Navy

photographers, Lt. White and Lt. Rude Osolnik encountered the

Cabildo’s barber.

Upon returning to the ship, they got the news a LCM ramp had

crashed down on this young man. He was taken to a hospital ship

in critical condition and the Cabildo sailed before learning of his

fate.

As 248 Dutch, Aussie and Javanese POWs had been assigned to

the Cabildo, the well deck bristled with tents containing cots.

The early arrivals, all of whom had been confined at least three

years, ate heartily, then enjoyed a movie. One of the Aussies

anxiously inquired: "Is Shirley Temple married yet?"

The following morning, Dr. Ted Berry, Gordon Dewart, Harry

Dick, Larry Blanchard and Maury White started interviewing

POWs for their history and medical records. It was tricky as many

of the Dutch enlisted had little or no English. Officers from the

Dutch East Indies served as interpreters, teaching us a few basic

words, which we pronounced poorly.

One of the interpreters laughed, insisting in Java they speak Dutch,

English, German, French and whatever native tongues needed so,

when attending school, the Javanese are so busy learning how to

talk they don’t have time to play sports.

Lt. Otten, of the Dutch air force, was a particularly good source of

information. Most prisoners spoke of the suffering the worst

atrocities after capture and before being brought to Japan, where

beating were the main and frequent punishment. Otten recalled

experiencing a two-hour lacing with a bamboo cane, then being

forced to kneel for 19 hours while under guard.

Americans for the most part being lazy about learning other

languages, it made a great impression when Otten and another

Dutch officer told of having learned to read Japanese papers by

listening to their captors speak of the news of the day, then

connecting oft-heard words to oft-used headlines to slowly gain

knowledge of the written language.

With the questioning done, and as part of a small convoy, we set

sail for Okinawa on the morning of Sept. 15 and soon experienced

the Navy at its grandest. A task group was entering the harbor as

we departed. As we passed by the USS New Jersey, battleship

sailors manned the rails in dress uniforms and the band played

stirring music to honor our newly-acquired human cargo.

Shortly thereafter, when alerted we were heading into a typhoon,

the convoy altered course and proceeded at full speed for about 4

hours. Unfortunately, the typhoon also altered course and

commenced belting the ships with winds of 65 knots, gusting to

about 125. Lt. Dick recalls a message from an admiral dispersing

the convoy and saying it was every ship for itself.

At that moment, and for the next several days, it was a blessing

having our ship under the command of Cdr. Holdorff, who had

guided many merchant ships through troubled waters. Giving way

when necessary, charging on when possible, that wise old sailor

somehow helped keep us afloat, intact, and out of the eye of what

we are led to believe is still considered the Big Daddy of typhoons

in that area.

For the first time, most of us experienced waves seemingly as tall

as the Empire State building, towering over an crashing across the

highest part of the ship. On an even keel the conning tower is 60 feet

above the waterline. With a constant roll of 25 degrees and as

much as 42 degrees, those sleeping in swing-and-sway hammocks

got some rest. Those of us in bunks tried tiedowns using light

lines, as it’s impossible to relax if clutching a mattress with

muscles tensed and one eye open to fend off careening furniture.

There couldn’t possibly have been any satisfactory solution for

those poor ex-POWs on cots. One of the most vivid memories

concerns 248 men coming off a three-year starvation diet suddenly

being offered all the food they wanted under conditions when at

least 80 percent of the Cabildo’s crew became sea sick. Time after

time, you would see a passenger load a tray, stuff extra biscuits in

his pockets, eat until it was necessary to rush to the rail and throw

up, then calmly cram down another biscuit.

It was a horrible trip, especially when this relatively

flat-bottomed vessel would take a particularly enthusiastic roll,

then stay tilted for what seemed an eternity, causing hundreds of

men to say silent prayers, requesting there be a roll back.

Few of the veteran sailors had seen anything like this angry sea,

except in movies featuring Moby Dick or Blackbeard the pirate.

Several reserves contemplating staying on in the regular Navy

quickly changed their minds.

Okinawa finally loomed in the distance on Sept. 19. Our

passengers, who may have been thinking the ride has been worse

than the prison camps, were no more grateful at journey’s end than

members of the crew.

Once close to shore, a very large ship, either Liberty or Victory,

could be seen high and dry on the beach, tossed there by the

horrendous power nature can unleash.

The only good thing about that typhoon is dozens and dozens of

ships in a 300-mile area now were able to write off just about any

missing gear or equipment as having gone with the wind.

Our passengers left us at Okinawa, then moved toward home in

stages. A few weeks later, Otten and several other officers were

encountered on the streets of Manila. All resembled pregnant

women in the mid-section, with arms and legs not yet fleshed out

from enjoying lots and lots of food.